![]() What is the correct way to attach a snorkel while scuba diving? Is it to put it on the left? On the right? Far forward on the mask strap? Farther back? Well, for most scuba divers, the correct answer is none of the above. To understand why, you first need to know a little bit about the history of snorkels and scuba diving — and about some very real drawbacks snorkels have that training agencies seem unwilling to acknowledge.

What is the correct way to attach a snorkel while scuba diving? Is it to put it on the left? On the right? Far forward on the mask strap? Farther back? Well, for most scuba divers, the correct answer is none of the above. To understand why, you first need to know a little bit about the history of snorkels and scuba diving — and about some very real drawbacks snorkels have that training agencies seem unwilling to acknowledge.

Why even have a snorkel?

Pick up any entry-level diver textbook. Turn to the page on snorkels. You will most likely find a statement to the effect of, “Snorkels allow divers to conserve air from their tanks while resting or swimming on the surface” — as though a snorkel is the only way to accomplish this. But is it?

Prior to 1980, the answer to this question would have been Yes. In the days before BCs, even properly weighted divers would have difficulty keeping their mouths out of the water when at the surface. The advent of horse-collar BCs didn’t improve matters much. Then, around 1980, we saw a dramatic shift away from horse-collar BCs to jacket-style and back-inflation units. That changed everything.

- Modern BCs made it possible for divers to comfortably rest on the surface with their heads completely out of the water.

- They also made it possible for divers who had to swim on the surface to do so on their backs, while breathing easily through their noses and mouths.

- With no snorkel in your mouth, you can actually talk to your buddies, thus improving communication and reducing the likelihood of confusion.

- A further benefit of not having to use a snorkel is that you no longer have to breathe through a restricted airway that also increases dead air space.

Not surprisingly, with the exception of dive instructors who are trying to follow standards, it’s unusual to see an experience diver with a snorkel attached to his or her mask. You almost never see a resort divemaster or instructor wearing one — and, keep in mind, these hard working professionals have vastly more real-world dive experience than the “experts” who work at most training agencies have. This should tell you something.

Why all the emphasis on being at the surface anyway?

Why all the emphasis on being at the surface anyway?

Many divers graduate their Open Water Diver courses thinking that being at the surface is a normal part of diving. It isn’t. The vast majority of diving these days takes place from boats. The norm here is that you enter and descend almost immediately, and try to surface as close to the boat as possible.

This is a good thing because, believe it or not, the surface does not represent safety. In fact, it is where most accidents happen. Statistics suggest you are safer under water, with plenty of gas in your tank, than you are when struggling against waves and currents at the surface.

As a dive boat captain, I frequently told divers that, with few exceptions, I wanted to see them with a regulator in their mouths from the time they entered until they were safely back on board. I would also tell them that, should they surface any distance from the boat, I did not want to see them struggling against waves or currents in an effort to get back. They were to inflate their BCs, make sure I could see where they were, then sit tight until I could bring the boat to them. I know that many dive boat captains do the same.

As a dive boat captain, I frequently told divers that, with few exceptions, I wanted to see them with a regulator in their mouths from the time they entered until they were safely back on board. I would also tell them that, should they surface any distance from the boat, I did not want to see them struggling against waves or currents in an effort to get back. They were to inflate their BCs, make sure I could see where they were, then sit tight until I could bring the boat to them. I know that many dive boat captains do the same.

In more than 40 years as a dive professional, I’ve only taught at or dove in a handful of places where long surface swims were unavoidable. These included a handful of rock quarries, the beaches of Southern California and Blue Heron Bridge in south Florida (and even there I do a surface swim only when working with students). Interestingly enough, most of the divers I encountered at these places were students in training and their instructors.

This being the case, it’s not surprising that most divers start leaving their expensive snorkels behind as they gain experience.

But isn’t it better to have one and not need it?

But isn’t it better to have one and not need it?

You’ve heard the saying: It’s better to have one and not need it than need one and not have it. This is the argument most often given for wearing a snorkel on every dive. The argument loses its validity, however, when you consider the following:

- At some sites — notably freshwater springs and similar sites where you are never more than a short swim from an exit or water shallow enough to stand — having a snorkel is simply ridiculous.

- At most other sites, the potential benefits of having a snorkel you will most likely never use attached to your mask can easily be offset by some very real drawbacks.

This second point is one that bothers me, as training agencies never seem to acknowledge the fact having a snorkel attached to your mask at all times can cause any number of problems, including:

- They’re distracting: Let’s face it; it’s annoying to have something constantly tugging on the side of your face. But distraction is not merely an annoyance; it’s a contributing factor in many dive accidents.

- They cause unwanted drag and interfere with mask fit: When diving in currents, the additional drag snorkels cause can go beyond simple distraction and annoyance. It can cause your mask to leak and lead to additional problems.

- They’re a potential source of entanglement: Do you dive around fishing line, abandoned nets or guidelines in caves or wrecks? Then that snorkel on your mask can easily get entangled.

- They’re easily mistaken for a BC inflator hose: Look at the bottom of most modern snorkels. It’s corrugated and it lies right next to your BC’s large-diameter inflation hose, making it easy to mistake the two. I have vivid memories of chasing after a diver who was plummeting from a depth of 6 m/20 ft to the bottom, some 40 m/130 ft below — all the while trying desperately to hit the power inflator button on his snorkel. Most resort divemasters and instructors can tell you similar stories.

- They interfere with wearing a hood: If you have a snorkel attached to your mask, your only option is to wear your mask strap outside your hood and to don your mask after your hood is in place. This can result in the edge of the mask skirt resting on the hood, causing leaks. It also makes it easier to lose a mask. If you ditch the snorkel, put your mask on first, then pull the hood up over the mask strap, it will reduce the likelihood of leaks and help prevent mask loss.

Still, you can understand why some divers may feel it would be nice to have a snorkel with you “just in case,” so long as it didn’t come with any of the problems just outlined. The good news here is that you can.

The better snorkel for scuba divers

The better snorkel for scuba divers

Most new divers start off by purchasing the worst possible snorkel for scuba diving — one far better suited for casual snorkeling by untrained divers. These “dorkels” are typified by large size, high drag and unnecessary gadgetry such as self-draining mouthpieces and snorkel-tip baffles or valves designed to reduce or eliminate water from entering. These are features that the casual snorkeler may appreciate — but which no serious freediver would tolerate.

The tragedy here is that many new divers, having been talked into a $60-$80 snorkel by a well-meaning dive store employee, may try to offset the additional expense by purchasing cheaper fins — fins that are invariably stiffer and harder to kick. What the divers will quickly discover, however, is that they would have been better off economizing on the snorkel and, instead, purchasing the best fins they could afford. Fins, after all, are something you use 100 percent of the time. Fancy “dorkels,” on the other hand, are soon abandoned.

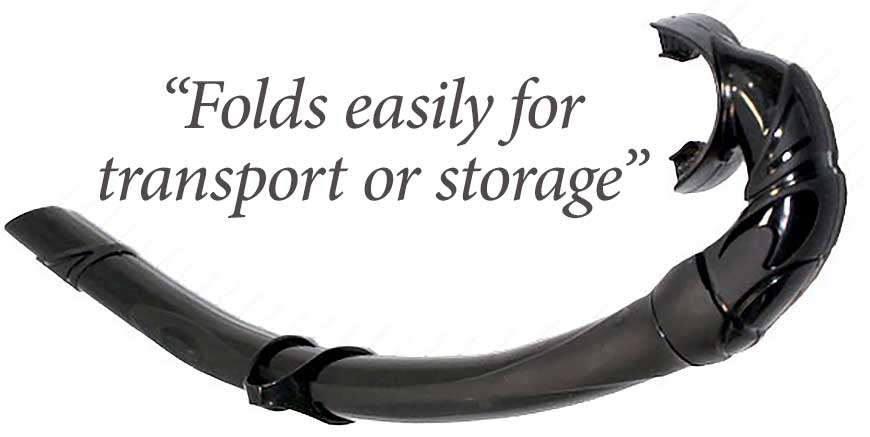

So what is the better investment? It’s one of the increasingly popular folding or “collapsible” snorkels. These snorkels offer several benefits, including:

- They are more affordable, seldom costing more than $40 and often half this or less. The money divers save here can be used to purchase better-quality fins or a dive computer — items that they will actually use.

- They are a vastly better snorkel for freediving. By getting rid of the self-draining mouthpiece and snorkel-tip gadgetry, these snorkels allow freedivers to perform a displacement clear — a critical skill for freediving efficiency.

- They create far less drag.

- Finally (and this is the most important point), they provide scuba divers with a snorkel they can easily carry with them at all times, simply by folding it up and putting it in a pocket. This is in direct contrast to the typical “dorkel,” which most divers will be tempted to leave at home.

The irony is that the only divers who truly need to go around with a “dorkel” attached to their masks are those who dive at one of those rare sites where surface swimming is unavoidable and who prefer to do so while swimming face-down, as opposed to swimming on their backs while breathing easily through their nose and mouth. And, when compared to the total population of divers, that’s a surprisingly small number indeed.

So what have we learned?

So what have we learned?

- The need for scuba divers to always have a snorkel attached to their masks largely disappeared in the early 1980s with the widespread adoption of jacket-style and back-inflation BCs.

- Most divers dive in situations in which there should be no need to swim on the surface or spend considerable time there. This further reduces the need for a snorkel.

- It’s understandable why a scuba diver may want to have a snorkel with him “just in case” — however, this desire is offset by the fact that wearing the type of “dorkel” most divers own comes with some very real drawbacks.

- The better solution is to carry a folding or “collapsible” snorkel, as this allows you to have a snorkel with you all the time, without suffering any of the problems associated with wearing bulky, high-drag “dorkels.”

- Folding snorkels have the further benefit of costing less, creating less drag and being better suited for freediving.

If you sell dive gear for a living, you may want to re-think how you sell fins, masks and snorkels.

- Start by getting students into the most efficient and easiest-to-kick scuba fins they can afford. Doing so will add immeasurably to their enjoyment of diving.

- To help justify the added expense of better-quality fins, explain that you are going to save the student money by getting him into a much more appropriate snorkel than what most divers buy — and end up never using.

You may also want to read these articles on “dorkels” and related topics: