If you think modern diver training really is all that modern because we now have eLearning or no longer teach dive tables, think again.

If you think modern diver training really is all that modern because we now have eLearning or no longer teach dive tables, think again.

Other than taking a lot less time, diver training has not changed significantly in the nearly four decades that I’ve been doing it. And, as a consequence, beginning divers are not much better today than they were in the 1970s. In many respects, they’re worse.

This is a shame because there are some fundamental changes that could not only allow you to make diver training more realistic, but empower you to create better divers in the process. And the best news is, in most instances, you don’t need to wait on your training agency to put these changes into effect. You just have to know what they are.

8 No more overselling the c-card

We’ve all seen the adds for the $99 scuba courses that tout “Lifetime Certification.” When you think about it, though, that’s about as silly as a college advertising a “Lifetime Diploma.”

- All a diploma does is testify to the fact that, at one instant in time, you were able to demonstrate mastery of a particular set of knowledge and skills. If, after receiving your diploma, you don’t enter the job market, don’t gain real-world career experience and don’t document that experience on a resume, your diploma quickly loses its value — and your career options become limited to asking, “Would you like fries with that, sir?”

- Similarly, if you toss your c-card into a drawer, never take any continuing education courses and never log any dives, after five years, your “Lifetime Certification” is essentially worthless.

Dive centers and instructors need to start explaining what a c-card really is: Something that, if unused, quickly loses its value.

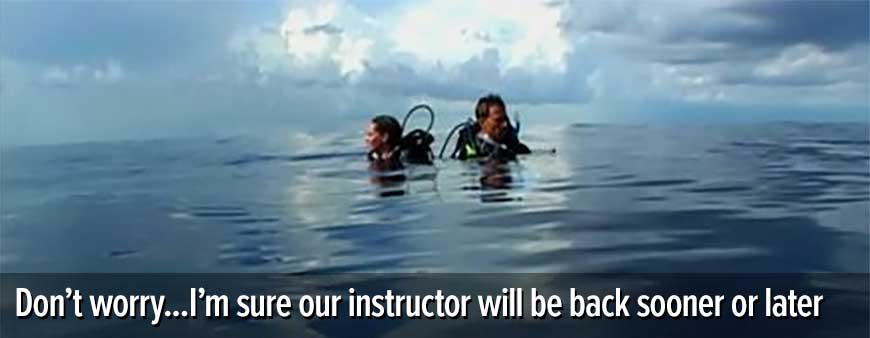

Another thing that dive centers, instructors and, yes, training agencies need to start doing is providing a more realistic perspective on just what entry-level certification qualifies you to do.

- Until you take that Advanced course or gain equivalent experience, you are really better off limiting your diving opportunities to ones where you can be under fairly direct divemaster or instructor supervision, such as is common at most dive resorts.

- Even with your Advanced card, you and your buddies are still better off diving from charter boats or at popular dive sites where, if an emergency arises, there will be plenty of other, more experienced divers around to help.

- Only when you have gained considerable experience and have taken formal Rescue Diver training should you and a buddy even consider diving someplace where there is no one around to help.

7 The end of “assembly line” diver training

Training agency standards typically allow a single instructor to take as many as ten students under water during open water training. Realistically, there is no way one individual can guide that many divers under water and still maintain adequate control and supervision.

As a consequence, the typical open-water training “dive” consists of little more than six to ten students, kneeling in a semicircle around their instructor, becoming increasingly cold and bored while waiting for their turn to perform yet another “skill.” Little, if any, actual diving is involved.

This sort of “assembly line” instruction is neither necessary nor safe. And it certainly does little to create better divers.

It’s important to remember that, while standards may limit students to no more than two or three dives in a day, there is no limit to the number of dives instructors may do. Therefore, when working with any more than four students, instructors are better off breaking them up into two or more smaller groups. This requires less time for doing “skills,” and provides more time for actual diving (and much-needed practice of buoyancy control).

Lahaina Divers, in Maui, was the best-run dive operation I’ve ever had the privilege of managing. This wasn’t my doing, but rather the result of policies and procedures put in place by company founder Blain Roberts, long before I arrived.

Among the rules we enforced at Lahaina Divers was that the maximum student-to-instructor ratio on any training dive — despite the warm water and exceptional visibility — was four to one. To this day, I maintain that this is the maximum number of students any instructor or divemaster can guide under even the most ideal of conditions. In low visibility, two-to-one is more realistic.

Nevertheless, I’ve frequently seen instructors in rock quarries try to take six or more students at a time on guided swims. This plain doesn’t work.

Even with a certified assistant bringing up the rear, the instructor can really only see and manage the buddy team immediately behind him. Similarly, the divemaster can only see and manage the buddy team immediately in front of him. Any buddy teams stuck in the middle are effectively unsupervised.

I can’t tell you the number of times, over the years, I’ve watched an instructor surface with his two students, the divemaster surface with his two students — and both of them going, “Where the Hell is everyone else?”

This happened to me numerous times when I first started teaching, because I didn’t know any better, and doing so was a common practice in the quarry where I taught. I was lucky; I didn’t lose anybody. Another instructor I taught with wasn’t as fortunate and, as a consequence, I got to work the first of a career total of eleven body recoveries (to date).

“Assembly line” diver training needs to stop. It’s not safe and it leads to poorly trained divers. As a standard if practice, four-to-one needs to become the maximum student-to-instructor ratio for all training dives involving beginning students.

6 No student left behind

Every dive instructor’s professional liability insurance policy has, among its warranties, a requirement that entry-level students never be left unattended at the surface or under water. This is also a training standard for most agencies and a standard of practice throughout the diving world.

Despite this, some diver training organizations require two skills in open water that all but guarantee students will be left unattended at some point. These are emergency ascents and underwater compass navigation.

Most training agencies seem to live in a fantasy world in which every instructor has at least two certified assistants to remain with divers who would otherwise be left, unwatched, while the instructor’s attention is focused on individual students. In reality, most instructors are lucky to have even one certified assistant. More often than not, they are completely on their own.

It might be one thing if both these skills were critical to diver safety. Unfortunately, they are not.

- There are several different ways students can get adequate practice of emergency ascent procedures in confined water. Repeating these exercises in open water accomplishes little, other than guaranteeing that, at some point, students will be left unattended at the surface or under water.

- Compass navigation is a seldom-used skill best left for the Advanced course, when students are already certified divers and, as such, can do simple compass navigation exercises with a buddy under indirect instructor supervision.

Beyond the obvious control-and-supervision issues, doing emergency ascent exercises in open water sets an absolutely horrible example for students.

In class, students are taught to ascend slowly and make safety stops — and to avoid “sawtooth” profiles. What they see in open water, however, is their instructor bouncing up and down like a yo-yo, at unsafe ascent rates.

During the years I ran Lahaina Divers in Maui, I had five instructors go to the chamber. While “operator error” was the chief factor in all these incidents, the other factor they had in common was that the last thing each instructor did before showing symptoms of DCS was conduct several emergency ascents with students. I’ve always wondered whether this was a contributing factor as well.

Unless you work with just one or two students at a time, there is almost no practical way you can follow most agencies’ standards and still avoid leaving divers unattended. This needs to stop. It’s unnecessary and it puts both students and instructors at needless risk.

5 Every ascent a slow ascent with a safety stop

If instructors doing emergency ascents in open water sets an egregiously poor example for students, what sets a good example? That would be, ending every training dive with a single slow ascent and a safety stop.

Bear in mind, students are more likely to remember what they see and do than they are what they hear you say.

In other words, actions speak louder than words.

What about alternate-air-source ascents? No problem. On two of your training dives, have divers ascend while sharing air. On one dive, a student will be the donor; on the other dive, he will be the receiver. The fact the ascent includes a safety stop just adds to the realism.

When you think about it, one of the reasons alternate-air-source ascents are the preferred solution to any out-of-air situation is that, given sufficient gas, both divers can not only make a slow ascent, but a safety stop as well.

You may as well practice it that way.

4 No “quarter turn back”

If you are still teaching this, you need to stop. Right now.

We’ve known for years that the practice of turning tank valves back a quarter turn has resulted in numerous close calls. Last year there was a documented case of it actually getting somebody killed.

Nearly all diver training materials now say, turn the valve all the way on. (Okay, NAUI’s apparently still say “back a quarter turn”…but give them a break; most of their training materials date from the last century.)

For a more in-depth discussion of why this is a practice that needs to stop, see The Quarter Turn That Kills.

3 The end of weight belts in diver training

Despite the fact weight-integrated models have accounted for the overwhelming majority of recreational BCs sold in the past 20 years, available evidence suggests most students still learn to dive using weight belts. In other words, dive centers and instructors are failing in their duty to train students how to use the type of equipment they are most likely to buy. That’s just plain wrong.

Dive center owners and instructors can give you all sorts of reasons as to why they should not put students in weight-integrated BCs — virtually all of which won’t stand up to scrutiny. For example:

”Most rental BCs aren’t weight integrated; therefore, if I don’t teach my students in weight belts, they won’t know how to use them.”

Remember that the reverse is true as well. If you don’t teach students in weight-integrated BCs, they won’t know how to use these, either.

Bear in mind, you can still show students who are using weight-integrated BCs what weight belts are, how to set up and use them properly, and how to remove them in the water. You can also set time aside for students to actually practice using them.

However, unless you put students in weight integrated BCs, they will never have the opportunity to learn to use them correctly.

This is not to say that weight belts don’t have their place:

- They provide fallback should you lose a BC weight pocket while on vacation.

- They are the weight system of choice for free diving. In fact, author Jon Hardy once suggested that breath-hold divers always wear a wet suit thick enough so that they would need to wear at least some weight. This way, in an emergency, they would be able to drop their weight belts and, thus, be guaranteed positive buoyancy.

However, as a primary ballast system for scuba divers, weight belts have several serious failings — the most obvious being they can be incredibly uncomfortable and inconvenient to use. Additionally:

- Weight belts can easily be covered up or trapped by other pieces of equipment — notably BC cummerbunds.

- Correctly dropping a weight belt in an emergency can require as many as seven separate steps. In contrast, dropping a BC weight pocket can require as little as three steps.

- Some diving accident victims have at least attempted to drop their weight belts, only to get them caught on other equipment.

- Under water, weight belts give you the choice of either dropping all of your weight on none at all. You may not drown, but your ballistic ascent may result in being bent or embolizing. Weight-integrated BCs, in contrast, generally give you the choice of dropping just a portion of your weight, thus ensuring a more manageable ascent rate.

Most damning of all is the fact weight belts concentrate the wearer’s ballast below the body’s natural balance point. This tends to drive your feet down, making it difficult (if not impossible) to maintain good buoyancy control and body position.

In other words, weight belts are potentially bad for the environment.

Weight belts are a piece of scuba equipment whose time has long passed. Diver training needs to reflect this.

2 The demise of the “dorkel”

Of all of the ridiculous ideas that diver training organizations persist in promoting, none is arguably more ludicrous than the notion that it is essential for divers to have an oversized adult toy strapped to their masks at all times.

This is not to say it’s a bad idea to carry a small, folding snorkel with you. At the bottom of a pocket. Along with your SMB, signal mirror and whistle — items you are more likely to actually need if stuck on the surface for any period of time.

What the training agencies apparently never figured out was that, with the widespread adoption of jacket- and back-inflation-style BCs over 30 years ago, the need for a “dorkel” when resting or swimming a the surface largely went away. Modern BCs allow divers to rest or swim comfortably with their heads completely out of the water, enabling them to breathe comfortably through their noses and mouths, and carry on conversations with buddies.

Resort divemasters and instructors are, unquestionably, among the world’s most experienced divers. As they dive nearly every day, and spend their time working with hundreds of real-world recreational divers, their experience vastly eclipses that of the typical training agency staff member.

So when was the last time you saw any of these hard-working professionals strap a dorkel to his or her mask? If you did, it was most likely because they were teaching a class and bound by archaic training agency standards (a requirement most of them blithely ignore).

Diver training needs to reflect how today’s best divers actually dive — not how somebody thought they should dive back in the 1970s. For a more in-depth discussion of this point, see The Sad and Sordid History of the “Dorkel.”

1 Making neutral buoyancy a habit, not a “skill”

Of all of the myths training agencies seem willing to promote (or, at the very least, refuse to dispel), none is potentially more dangerous to divers or harmful to the environment than the idea that new divers simply can’t develop adequate buoyancy control skills during entry-level training.

After all, were beginning divers to actually learn real buoyancy control, how would agencies sell all those remedial buoyancy control Specialty Diver courses?

The fact is, beginning students really can develop good buoyancy control habits, even within the limited time frame of most modern scuba courses. But you can’t do so by continuing to teach scuba the way it was during the last century.

The key is to make buoyancy control like breathing continuously or equalizing early and often during descent: A habit students practice continuously, as opposed to a “skill” they perform sporadically.

Doing so is neither difficult nor time consuming. Explaining it, however, requires more space than we have here. To learn more, see Four Keys to Teaching Real Buoyancy Control.

Among the biggest reasons so many new divers drop out shortly after certification is that they are never truly comfortable in the water. Developing students’ confidence in their ability to control buoyancy can go a long way toward preventing this from happening.

Becoming an Agent of Change

If you want to wait for your training agency to implement these changes, we hope you have a lot of time on your hands. Fortunately, most of these are things you can do right now. For example:

- There is nothing stopping you from presenting students with a more accurate assessment of what certification really is.

- You won’t violate training standards by taking fewer students ib the water at a time.

- You can stop teaching the dangerous “quarter turn back” procedures and make sure as many training dives as possible end with a single, slow ascent and safety stop.

- As soon as finances allow, you can get students out of weight belts in into weight-integrated BCs that are more typical of what they will buy and use.

- Even if your training agency insists that you and your students must have snorkels, it doesn’t mean you have to wear them on your masks.

- Just because you were taught to teach counterproductive exercises such as fin pivots and Buddha hovers, it doesn’t mean you can’t abandon these outmoded “skills” in favor of teaching real buoyancy control.

About the only change you may not be able to make if you choose to remain with your present diver training organization is the requirement that you teach emergency ascents and underwater compass navigation in open water.

Be aware, however, that there are training agencies who do not require these skills. Consider trading up or, at the very least, letting your current organization know that you may jump ship if they insist you keep teaching skills that force you to leave students unattended.

It’s a rare instructor who does not want to create the best divers he or she possibly can. The power to do so is in your hands. You just have to make the decision to use it.

BTW, feel free to leave a comment. Just remember that this is not Facebook. Depending on what you say, I will either praise your good judgment or ridicule you unmercifully in front of others. Your call.