Most dive instructors would agree that it is far harder to break bad habits than it is to never allow those habits to form in the first place. It’s why we are so adamant about students not putting masks on foreheads or leaving tanks standing upright unattended. Yet, despite this, most instructors allow students to form four of the worst possible habits just by continuing to teach “the way we’ve always done it.” Some divers manage to break these habits with time; many never do.

Most dive instructors would agree that it is far harder to break bad habits than it is to never allow those habits to form in the first place. It’s why we are so adamant about students not putting masks on foreheads or leaving tanks standing upright unattended. Yet, despite this, most instructors allow students to form four of the worst possible habits just by continuing to teach “the way we’ve always done it.” Some divers manage to break these habits with time; many never do.

It doesn’t need to be this way. Your students can form good habits right from the start — habits they won’t need to break later on. You just need to know what the four bad habits are, why they’re a problem and how easily you can help students avoid them.

Let’s look at that now.

Being overweighted

What it is: If your students are wearing any more weight than is needed to maintain neutral buoyancy in shallow water, they are overweighted.

Why it’s a problem: Where to begin? Overweighting students is so very wrong, on several levels.

- Students end up believing that being overweighted is what feels “normal.” Think about this. A properly weighted diver in a thick wet suit will generally not be able to sink just by venting his or her BC. The diver should also need to make a full exhalation to initiate a descent. Yet most new divers come out of their certification class believing that, if they can’t descend just by venting their BCs, they need more weight.

- It greatly complicates buoyancy control. A diver who is carrying just 1 kg/2 lbs more than is needed may have to make as many as twice the number of buoyancy adjustments with his or her BC than a diver who is properly weighted. Why? Because instead of just having to compensate for exposure suit compression and expansion, that diver will also need to compensate for the compression and expansion of the air which is in his or her BC solely to offset the unnecessary weight. A severely overweighted diver may experience so much excess air compression and expansion that he or she begins yo-yo-ing, and buoyancy control becomes all but impossible.

- Overweighting is dangerous. Even though a problem may first manifest itself under water, most diving accident victims still manage to make it to the surface. Many diving accidents simply begin on the surface. However it happens, the difference between those divers who survive and those who perish is often weighting. Properly weighted divers seldom need to struggle to remain at the surface. If an overweighted diver, on the other hand, forgets to inflate a BC or drop his or her weights, that diver may ultimately lose this struggle and drown.

How to fix it: Before assailing students with a litany of skills in shallow water, invest the time to get each student weighted for neutral buoyancy. This may take a few minutes, as students may be apprehensive or excited and, as a consequence, breathing more deeply than normal. Have students breathe from their regulators while swimming in shallow circles and experimenting with how breathing affects buoyancy. If stuck at the surface, have students first try exhaling fully and then relaxing before simply putting more weight on.

The only “skill” you need to cover with students prior to doing this is breathing from a regulator. Regulator recovery and clearing, along with mask clearing, can wait. The students are in shallow water. If they have a problem, they can simply stand up.

We are often asked what will happen when students who are weighted for neutral buoyancy with full cylinders start to empty those tanks and become lighter. To start, if this actually becomes a problem, well…this is why we all keep those extra weights by the edge of the pool. Most of the time, however, as that first pool session progresses, students become more relaxed and breathe less deeply. This can offset their cylinders’ increase in buoyancy.

Another question we get has to do with the fact students often take a deep breath prior to attempting skills such as regulator recovery and mask clearing. If weighted for neutral buoyancy, this will cause them to float up. You can prevent this from happening by having students hang on to a heavy object, such as a 4 kg/10 lb barbell, with one hand while doing the skill. This will have the added benefit of teaching students to do critical skills one-handed.

When you begin your classes by first making sure students are weighted for neutral buoyancy, you start seeing immediate benefits.

- Students get in the habit of being properly weighted rather than in the habit of being overweighted.

- Students will be able to learn and demonstrate core skills while neutrally buoyant — just as they will need to be able to do in open water, where there is generally no training platform or sandy bottom to kneel on.

- Students immediately see the role that proper weighting and breath control play in the overall buoyancy control equation. In fact, doing so makes learning to control buoyancy — and most other skills — easier.

Being out of balance

What it is: Your students are out of balance if their feet are constantly sinking and their bodies keep shifting from horizontal to vertical.

Why it’s a problem: As divers, your students need to get in the habit of not only being neutral, but horizontal. It is hard to form this habit if their equipment is constantly forcing them into a vertical posture.

How to fix it: There may be several things that need to happen in order to fully solve this problem.

- Ditch the weight belts: Weight-integrated BCs have accounted for well over 90 percent of the recreational BCs sold in the past 20 years. Why would anyone not teach students how to use the type of equipment they are most likely to buy? The added benefit of teaching students in weight-integrated BCs is that, unlike weight belts, which concentrate ballast below your body’s natural balance point and tend to drive feet downward, weight-integrated BCs concentrate ballast at your body’s natural balance point, making it easier to stay horizontal.

- Use trim weights: If the BCs you teach with have trim weight pockets, use them. If not, consider attaching add-on trim weight pockets to the BC cam band. Most divers need at least some weight higher up on their BCs to remain horizontal.

- Use full-length exposure protection (or none at all): Shorty wet suits or — worse — wearing just the top of a two-piece wet suit adds lift to the upper portion of the body while allowing the feet to sink. In contrast, full-length suits tend to add critical lift to the legs. If fortunate enough to teach in extremely warm water, you may discover that diving with just a rash guard or skin accomplishes much the same thing.

- Move tanks upward: Aluminum cylinders have an ungodly amount of metal at the bottom, making them unusually tail-heavy. When tanks end up hanging half way down students’ backs, it only makes matters worse. Tanks only need to be low enough that students aren’t constantly hitting the regulator first stage with the backs of their heads. As an added benefit, this makes it easier to recover regulators using the reach method.

Dive retailers frequently tell us they can’t do some of these things for any number of reasons (although the real reason is that they just don’t want to invest the money). Here are some of the claims, and the reality that goes with them.

- “Most rental BCs are not weight-integrated, so we have to teach students in weight belts so they know how to use them.” That’s actually true — but you need to teach the proper use of weight-integrated BCs for the same reason. You can do both. That portion of the course where you introduce basic freediving skills is a great time to teach proper weight belt set up and use, as students will not be getting their weight belts hung up on BC jackets or other equipment. (In case you haven’t figured it out yet, weight belts really do not work well with modern BCs — and haven’t since the early 1980s.)

- “But I make money selling students weight belts and don’t want to give it up.” You don’t have to. Every diver should own and travel with a simple weight belt in case they lose a weight pocket on a trip and replacements are not readily available. Do you need to be selling students US$50 pocket-style weight belts? No. Have students put the money they save on more basic weight belts toward better-quality fins or an entry-level dive computer — items they genuinely need.

- “I don’t want to invest in full-length wet suits for the pool; students will just wear them out.” Then don’t. Many dive stores do not supply any sort of exposure protection for the pool, but encourage students to invest in a full-length, 3 mm wet suit. These are something every diver should own, if only for use on vacation travel.

Scrimping when it comes to rental equipment is one of the worst mistakes dive retailers make. It sends the message that, “You really don’t need anything other than the cheapest gear available.” Students will take you at your word on this. In fact, they will often take it a step further, and buy all of their gear from an online discounter.

Being in constant contact with the bottom

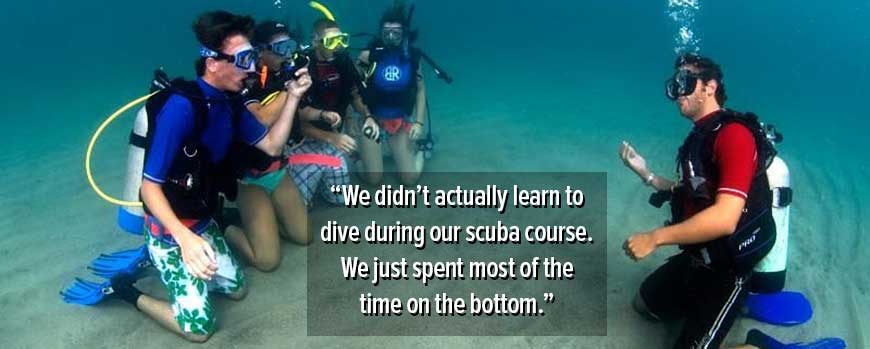

What it is: Students spend the majority of their time, both in confined and open water, standing, sitting or kneeling on the bottom.

Why it’s a problem: At least three reasons here:

- Students get in the habit of being on the bottom — a habit that carries over into the diving they do following certification. The environment suffers as a result.

- Students who get in the habit of being on the bottom also get in the habit of being vertical.

- Spending most of the course on the bottom means students have insufficient time to develop real-world buoyancy control skills.

How to fix it: The first step in fixing this problem is to establish and enforce a new rule. That is, whenever students’ heads are under water, their knees, the soles of their feet and their butts are not to the touch bottom. If students absolutely must be in contact with the bottom, it is to be with fin tips and fingertips only. Additionally, students are to maintain a horizontal body position whenever feasible (which is pretty much all the time).

The sole exception to this rule would be in the case of skills such as scuba unit removal and replacement, which are difficult for beginners to do unless firmly planted at the bottom of the deep end. You, on the other hand, should be able to demonstrate this skill — and any other — while maintaining neutral buoyancy.

Beyond just enforcing a rule, preventing students from getting in the habit of constantly being on the bottom requires adopting a new mindset. That is, making buoyancy control a habit and not a “skill.” If you follow the steps outlined thus far, students will get in the habit of being neutral from the start. You just have to avoid the temptation to plant them on the bottom like rocks in order to teach most skills.

Becoming button-dependent

What it is: This is when students associate the art of buoyancy control solely with pushing buttons on a BC.

Why it’s a problem: Buoyancy control — real buoyancy control, that is — involves far more than just pushing buttons. Real buoyancy control involves balanced equipment, proper weighting, breath control and active participation by divers. BC use is certainly part of this, but it should be limited solely to compensating for exposure suit compression and resting or swimming on the surface.

How to fix it: The first step is to quit equating BC use with buoyancy control. While it is certainly one aspect, students need to understand that they learned the most important steps in controlling buoyancy when you introduced them to proper weighting and breath control at the start of the course.

The next step is to quit teaching counterproductive “skills” such as fin pivots and Buddha hovers. To start, the only way students can do these skills is if overweighted and in equipment that makes their feet sink — conditions that should never be allowed to exist in the first place.

The more effective way to teach BC use under water is to start by teaching students how to quickly and correctly vent air from their BCs. (Adding air to a BC is the easy part; you just push a button. Whsy students generally find much more challenging is learning where to find their BC deflation controls and position their bodies so that no air remains trapped in the BC.)

Once your student know how to prevent runaway ascents, have them experiment with venturing into the deep end while adding air in their BCs in small bursts. Have them make repeated trips from shallow to deep and back, until they get a feel for when to add air and when to vent.

This, by the way, was how those of us who were present when BCs first appeared taught ourselves how to use them. It was an effective way to learn then and remains so today. And, unlike fin pivots and Buddha hovers, it is vastly more realistic and does not result the formation of bad habits.

Does it work?

If you are new to this way of teaching, you may be wondering how all this can work. After all, much of it runs counter to things you were told instructors “must” do, such as overweighting students so that you can maintain “control” by planting them firmly on the bottom. To this, we can only say, “…and how is that working out for you?”

Seriously, have you seen the way most newly certified divers look under water? Those of us who drive dive boats for a living have, and I can tell you that we are not happy with what we see. Is that how you want us to see your students?

It doesn’t have to be this way. We’ve been training in ways that teach real buoyancy control while developing and reinforcing good habits for nearly a quarter century. And we can tell you, it works. As you can see from the comments on our blog articles and Facebook posts, there is a growing number of dive instructors — and training agencies — who agree.

Do you want to be left behind? Do you want yours to be the kind of students dive boat crews and other dive professionals talk about behind your back? Then don’t. Make fundamental changes in how you teach and accept nothing less than the best from your students. You’ll feel better about teaching, your students will be safer and have more fun, and the environment will benefit in the process.

Learn more

If you would like to learn more about new and different ways to teach, you may find these articles helpful:

- Four keys to teaching real buoyancy control

- Don’t make overweighting your invisible assistant

- The ultimate weight check

- Seven reasons why Buddha hovers are bullshit

In case you were wondering, none of the photos appearing in this article were staged. All were photos that instructors and stores posted on social media or on websites (as though they were actually proud of what you see). Fortunately for us, copyright law allows for the “fair use” of such images for editorial purposes. Still, we don’t want to embarrass anyone by outing them publicly, so we won’t shame the perpetrators by naming them. As a friend once said, “These are not bad people; they just have some bad behaviors.”