Lawsuits are something you expect to happen to The Other Guy. Certainly not to you. You’re a good instructor. You teach responsibly and follow standards. Your students love you and would never dream of actually suing you. And, in your fantasy world, peace and harmony abound, and every child gets a pony. Yeah…right.

Lawsuits are something you expect to happen to The Other Guy. Certainly not to you. You’re a good instructor. You teach responsibly and follow standards. Your students love you and would never dream of actually suing you. And, in your fantasy world, peace and harmony abound, and every child gets a pony. Yeah…right.

Then, as they say, there is reality. And that reality is, even the best of instructors make mistakes. Even the best instructors have incidents. And even if you are utterly blameless, you can still be sued. When that happens, the only thing we can guarantee is that it will be the most utterly miserable experience of your entire life. ‘Best be prepared.

In this article, we are going to examine some of the bitter realities of risk management. These are things of which too many diving educators seem blissfully ignorant. It’s not going to be pretty.

Two disclaimers going in:

- First, I’m not an attorney; this is not to be construed as legal advice. All we are doing here is reporting on information presented at most agencies’ instructor training programs. If you want a legal opinion, consult an actual attorney.

- Second, the information presented here pertains almost exclusively to the United States, a nation with perhaps the most bizarre and irrational legal system on the planet. If you are fortunate enough to live and teach in a country with a more sane and logical legal system, count yourself lucky.

7 There is no defense against being sued

While teaching defensively can help lower the odds of you losing a lawsuit, it can’t prevent a lawsuit from being filed in the first place. The only realistic answer to the question, When can I be sued? is:

- Any time

- Any place

- For any reason

What can we say? God bless America.

- While it’s unlikely that an injured student may want to sue you, he or she may not have a choice. If faced with unpaid medical bills, loss of income or other financial hardships, a student may feel as though he or she has no recourse other than to try to collect from your insurance.

- When it’s surviving family members, the situation is even worse. They most likely don’t know you, much less feel the loyalty to you that most students do. All they know is that a loved one (who never made any mistakes) is now dead. This can only be someone else’s fault — in other words, yours.

Although it is always possible that a student injury or fatality may not result in a lawsuit, you have to assume that it will. Current liability insurance is vital. You are nuts if you teach without it.

Additionally, given that an injured student may not really want to sue you, but feels that he or she has no choice because of uninsured medical bills, you should have them take advantage of Divers Alert Network’s free Student Membership program before any in-water training takes place. This provides all of the benefits of normal DAN insurance for the duration of their course. And, because it is free, it’s a no-brainer.

6 The outcome with have little to do with the facts

You taught defensively. You followed standards. You kept student-to-instructor ratios low and made certain students were never unsupervised. In fact, you can’t think of anything you really did wrong — other than find yourself with a student who refused to listen and follow directions. This should be enough to make sure you win…right?

Get a freakin’ clue. This is America. It doesn’t work that way.

The plaintiff’s attorney doesn’t give a shit what the facts are. All he cares about is winning at any cost. Trial lawyers are masters of spinning the facts until, in the eyes of a jury, Mother Theresa herself comes across as worse than the most depraved ISIS Jihadi. (Okay, as it turns out, Mother Theresa wasn’t quite as saintly as once thought…but you get the idea.)

Things get even worse if the victim is someone whom juries finds sympathetic. Was the victim young, female and attractive? Good luck with that.

It won’t matter that she lied on her medical form, had six different prescription (or nonprescription) drugs in her system at the time of the accident and had partied heavily the night before. Juries will most likely feel it unlikely that she could ever do anything wrong. You, on the other hand…

5 It’s not likely you will “win”

Okay, let’s say you did everything right, and there is a preponderance of evidence to support this. Surely your insurance company will go to the mat, fighting with every ounce of their being to exonerate you…right?

‘Sorry. Doesn’t work that way. Even with the evidence overwhelmingly in your favor, it can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars for your insurance company to secure a verdict on your behalf. Compared to this, the opportunity to settle for a few tens of thousands will seem like a bargain to them.

Don’t take it personally. It’s just business.

4 Don’t sabotage yourself going in

Training agencies and their insurance carriers get to see all the incident reports filed by their instructors. Reading these reports often leads to further injuries caused by repeated face palming and eye rolling. More than one training agency executive has been overheard saying, “How can anyone be so utterly stupid!” (Remember: Ignorance can be educated, but stupid is forever.)

A thorough discussion of all of the errors of commission and omission committed by dive instructors over the years would take far more space than we have here. A college semester might be better suited. We are going to focus on just one thing: Paperwork. Here are just a few instances that have made our eyes roll.

Waivers

A dive store owner I once knew thought he was pretty clever. He was determined to ensure the waiver and release forms his entry-level students signed would hold up in a court of law. So here is what he did:

- Students were not asked to sign waivers until the first night of class.

- Before doing so, they watched his training agency’s very thorough risk-awareness video.

- Then, before actually signing the form, he would have his instructors read every word of the waiver aloud.

- Only when this was complete and the students were fully informed of all possible risks were they allowed (or, more accurately, told) to sign the form.

Pretty bulletproof…right? Well, not exactly.

During most agencies’ instructor courses, candidates are warned of the dangers of having students and divers sign waivers “under duress.” For example, if a dive operator waits until the boat arrives at the dive site to have passengers sign waivers, it can be argued that they did so under duress because, at this point, what other choice did the have? In the case of this dive store owner, by the first night of class, students had already:

- Paid for the course in full

- Purchased mask, snorkel, fins and boots

- Invested six or more hours completing the self-study requirements

Additionally, some had also paid for a doctor visit in order to get a signature on the required medical form. Failure to sign the waiver at this point would cause them to lose a considerable investment of both time and money.

If that doesn’t constitute “duress,” it’s hard to imagine what does.

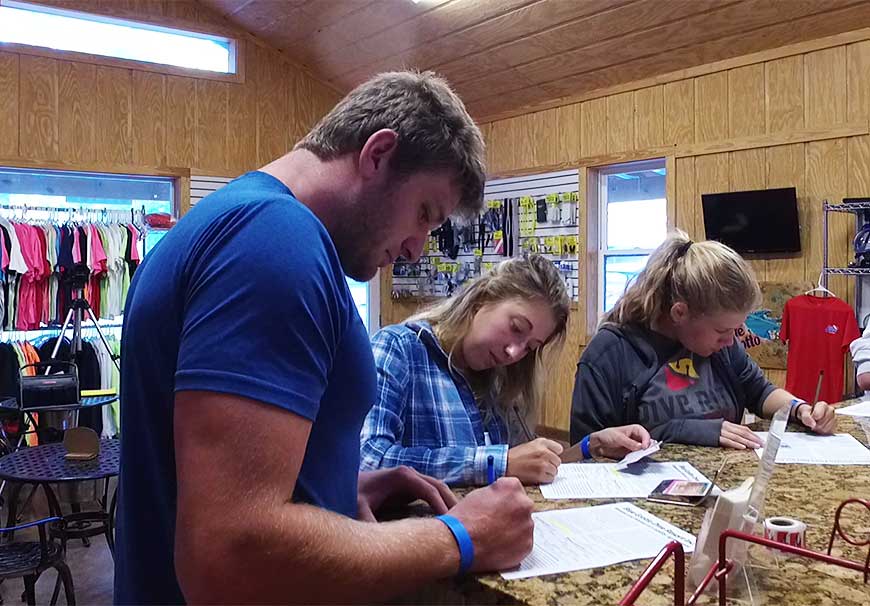

The best time to have students and divers sign waiver forms is after they have been fully informed of the risks inherent in diving, but before they spend a single penny or invest a single minute of time. The dive store owner in this story would have been better off having prospective students watch the risk-awareness video and sign the waiver form before they paid for class, purchased equipment or invested any time in training. You should do the same.

Speaking of risk awareness, SSI has an absolutely excellent video, designed to be seen by prospective students before they sign any waivers. It’s non-agency-specific and available for anyone to use on You Tube. Here it is:

I strongly encourage any instructor, of any agency, to have prospective students watch this video prior to signing waivers, paying course fees or purchasing equipment. There is even a second video in this series that is designed for students to see before they move from confined to open water.

Now, before any readers jump in the Comments section and start nit-picking, yes, these videos aren’t perfect. Among other things, they show students kneeling on the bottom and sporting dangling equipment. Whoever wrote the script also needs to learn the perils of using passive voice, and there is SSI’s penchant for using non-standard diving terminology. Still, these flaws are minor and pale in comparison to the benefit of having students who are fully informed of risk.

Given that there is no cost associated with using these videos, you would be foolish not to.

Medical forms

Of all the paperwork associated with defensive teaching, no other form seems to be as poorly understood as the Medical History form. Just to re-cap what you should already know:

- The form must be completed and signed prior to any in-water training and, preferably, prior to the start of the course.

- If students answerYES to any question, they must get a physician’s approval prior to any in-water activities. No exceptions. And that physician’s approval must be where indicated on the Medical History form. A verbal okay won’t cut it.

- Students must physically write out the words YES or NO to each question. The use of check marks, Xs or lines through multiple items completely invalidates the form. Make certain prospective students clearly understand this before they even pick up a pen.

Instructors in continuing education courses often ask whether a Medical History filled out less than twelve months before is still valid. That’s the wrong question to ask. You should have students complete a new Medical History at the start of every course to ensure their medical condition has not changed since the last course.

- If students can still answer NO to every question, you’re good to go.

- If students answer YES to a question, they will of course need a physician’s approval.

This is where the twelve-month rule comes into play. If the student has a medical form that is signed by a doctor and less than twelve months old, it is generally considered valid — provided the medical form the student just completed shows no change in health. Otherwise, they will need to get a physician’s approval again.

Most training organizations use the RSTC/UHMS form. The beauty of this form is that it does not require instructors to make medical judgements they are not qualified to make. A YES means the student goes to the doctor. No exceptions.

The only down side to the RSTC form is that it is designed to be printed on both sides of a single sheet of paper. Unfortunately, students frequently download this form and print it on two separate sheets of paper. The problem is, how to you prove in a court of law that the medical history the student completed on the first page of the form actually goes with the student and doctor signatures on page two? Make sure you let students know the form is only valid if printed on a single sheet of paper.

Are you ready for the epitome of “dumb?” I once ran into a surprisingly prominent training agency who, for whatever reason, had elected not to use the RSTC form or one very much like it. The form they had created (all by themselves!) listed many of the standard contraindications to diving. But it also contained totally innocuous questions such as Do you wear glasses? and Do you wear dentures? It was up to the instructor to decide which of these questions indicated a condition requiring a doctor’s approval and which did not.

Baffled by this, I decided to call the agency’s headquarters and ask what I should do about a student who had answered YES to a condition I know absolutely requires a physician’s approval. (I knew this not only because it was on the RSTC form, but because I suffer from the same condition myself.) According to the “expert” I spoke with, it was up to me to decide whether or not a doctor’s approval was needed.

I’m sorry. You can’t make up stories about this level of sheer stupidity.

Moving on, here are some things we’ve actually heard or seen instructors say or do that represent a nearly equal level of stupidity when it comes to Medical History forms:

- Allowing students to fill out the form incorrectly, or printing it on two separate sheets of paper.

- Allowing students who answered YES to a question on the form to participate in in-water training, with the understanding that they would get a doctor’s approval “as soon as possible” or before open-water training.

- Not requiring students to get a physician’s approval if they answer YES to one or more questions.

- Telling students to outright lie on the form so that they don’t have to get a doctor’s approval. (Do you honestly think no one will remember hearing you say that?)

Student records

The late Jon Hardy was Executive Director of NAUI during its zenith in the late 1970s. NAUI is often regarded as being The Dinosaur Agency, but Jon was surprisingly progressive. Following his tenure at NAUI, Jon did a variety of things, including acting as an expert witness in a number of cases involving dive instructors. As such, he became an expert at defensive teaching.

One thing Jon told me that rang true had to do with student records. What Jon said was that you want to make certain all your records show is the date a student demonstrated satisfactory performance of a particular skill. The last thing you want to do is grade that skill on a 1 to 5 or similar scale.

The reason for this is that, say, you gave little Mary a 3 for mask clearing. I mean, that’s like getting a C in Algebra — a passing score…right?. Shortly after training, little Mary panics and embolizes due to a flooded mask. In the trial that ensues, her parents’ lawyer rips you to shreds. “Why, Mr. Instructor, did you pass little Mary on mask clearing when your own records show her mask clearing skills were less than perfect?”

What many experts recommend is that, before you sign a student off on any skill, he or she must be able to demonstrate the ability to perform that skill:

- On demand

- Repeatedly

- Without significant error

- Without undue stress

The fact a student has reached this point doesn’t mean it’s okay to stop practicing this skill. After all, repetition is key to learning. It does mean, however, that it is probably okay to sign the student off for that skill.

If your student can’t demonstrate this level of competency, you are best off leaving the student record blank until he or she can.

3 It won’t go away overnight

When something truly bad happens in our lives, we usually just want it to go away as quickly as possible. No such luck here.

- To start, a surprising amount of time may pass between the incident itself and when the plaintiff(s) actually file suit. In most jurisdictions, there is a statute of limitations dictating the amount of time potential plaintiffs have to file suit. It is not unusual for them and their attorneys to wait until the last minute to do so. This gives the plaintiff’s side more time to discover potentially damning evidence. It’s also time that you can find yourself suspended in limbo, counting the days until the time limit expires and you, hopefully, are in the clear.

- Once filed, a suit can drag on for years. Lawyers love this, as it provides them with more opportunity to rack up billable hours. It also increases the likelihood the other side will cave in and settle. For you, it will be a time when every aspect of your life is overshadowed by a dark cloud that won’t go away.

Make no mistake: These are likely to be some of the worst years of your life, during which all you will want is for it to be over. All we can say is, be prepared for a long, drawn out battle.

2 Your teaching career is most likely over

In theory, if you have done nothing substantially wrong, your training agency has not suspended or expelled you and your attorneys are optimistic about the outcome, there is no reason why you can’t continue to teach until the case settles. It’s just not likely to work out that way.

- To start, the experience of being sued for personal injury or wrongful death can be absolutely soul-crushing. You are going to be filled with doubt (“Did I do absolutely everything possible to prevent this?”). And if, by chance, you don’t have any doubts of your own, the plaintiff’s attorneys will be happy to supply them for you. Odds are, you did at least one thing wrong — even if it did not contribute substantially to the incident. After all, you’re only human. That error is going to eat at you and will be one of many factors that combine to take all the fun out of teaching.

- You can bet the plaintiff’s attorneys will be in touch with your past students, your friends, your employer and your fellow instructors. They will be asking questions specifically designed to get these individuals to divulge information — factual or not — which will help their case. They may even threaten fellow dive professionals with being named as co-defendants if they do not roll over on you. We’ve seen more than one friendship ruined this way.

- If you teach for a store, resort or any other sort of business, don’t be surprised if your services are no longer needed. After all, what business wants the stigma of employing a “killer” instructor?

- Similarly, your reputation as a dive professional will be shot to Hell. You may have, in fact, done nothing wrong. But people don’t know that. And, if you haven’t, why are you being sued?

Most instructors teach largely for fun. A single incident like this can easily take all the enjoyment out of teaching. Don’t be surprised if, even though you may ultimately prevail, your incentive to ever teach again goes right out the window.

1 A million bucks ain’t enough

The real value of professional liability insurance isn’t that it can help pay any judgement or settlement. Rather it is that it will pay to provide you with a thorough and vigorous defense. And the tab for defending a suit, even a baseless one, can easily run hundreds of thousands of dollars. We know of cases where the cost of defense exceeded one and a half million.

Most dive instructors carry one million dollars in professional liability coverage. Agencies offer this because it makes premiums more affordable. The problem is that, in this day and age, it’s no longer enough. The current thinking is that you are going to need at least two million dollars in coverage to adequately provide for the cost of defense.

If this kind of coverage is available to you, buy peace of mind and pay the extra for it.

Looking for a ray of sunshine? Guess what?

Yes, we know. What you’ve read thus far may seem sufficiently depressing to make you want to quit teaching. And make no mistake: If you are involved in any sort of incident resulting in personal injury or death, it is going to be a long, drawn out and utterly miserable experience.

Every aspect of life entails risk. This is the risk we face as dive professionals. There is no guarantee you will survive your next dive or that your students will survive your next class.

The only good news is that, as diving is actually fairly safe, the odds of you being involved in this sort of incident are slim — especially if you teach conscientiously, follow standards and provide adequate supervision.

Nevertheless, you have to accept the fact that “feces occur.” And, in the unlikely event they do, you have to be prepared for a rough, rocky road that will change your life forever.