What happens when the people we rely on most to provide good role models for new divers drop the ball? That’s easy. The divers get bad information and, as a result, make poor decisions. This is why being a role model is so important.

What happens when the people we rely on most to provide good role models for new divers drop the ball? That’s easy. The divers get bad information and, as a result, make poor decisions. This is why being a role model is so important.

Consider the role dive instructors play in this process. We not only expect professional diving educators to follow standards and adhere to safe diving practices, we also expect them to wear and use equipment that is complete, well-maintained and typical of what new divers should invest in themselves.

Mind you, we’re not saying that every new diver has to buy exactly the same equipment as his or her instructor uses; however, if they choose to do so (and they often do), students should be confident that they are investing in equipment that will not only meet their needs, but is safe, reliable and which, with proper maintenance, will provide years of enjoyable service.

Now consider this: Are there role models a new diver might consider to be an equal or even greater authority than his or her instructor? Two possibilities come to mind: The instructor’s training agency and major dive magazines.

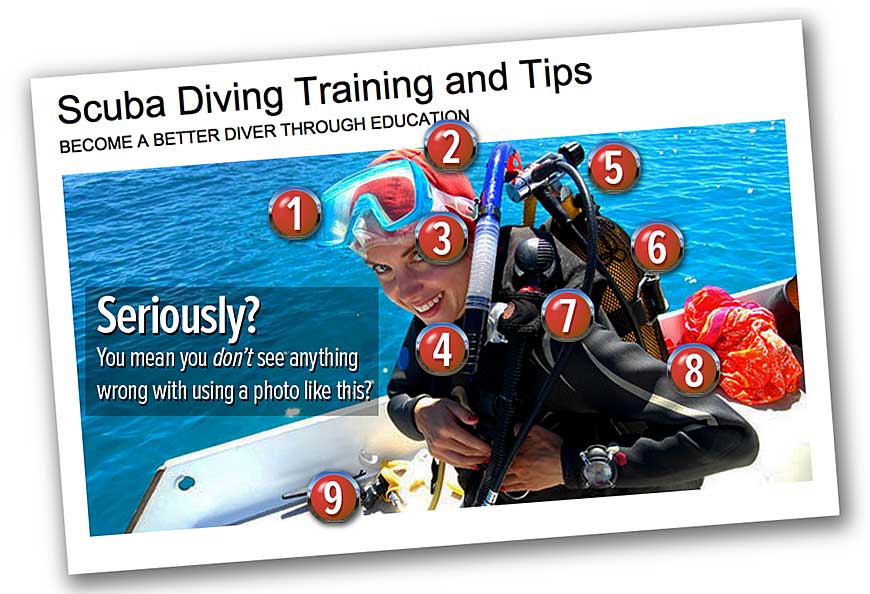

Imagine our dismay, then, when the following image appeared on one of the main pages of a major training agency’s website and on the website of one of the two leading dive magazines.

What is especially troubling is that, on the magazine’s website, this photo was used as the lead-in for a section entitled Scuba Diving Training and Tips: Become a Better Diver Through Education. Seriously?

It would be one thing if this were someone’s vacation photo they had posted to Facebook. Nitpicking or belittling such a photo publicly would be impolite at best and downright cruel at worst. (Although a private message to the unwitting diver with some specific suggestions might help that diver become better.)

A training agency or dive magazine using this image, however, is and entirely different matter. Consider the messages using a photo such as this sends to new divers.

1 “It’s okay to put your mask on your forehead”

To be honest, I’ve never bought into the whole “sign of distress” argument. Too many divers and, especially, snorkelers do this to be able to say that anyone with a mask on his or her forehead is panicking.

Potential mask loss is a different issue. If you get in the habit of putting your mask on your forehead odds are, sooner or later, you will lose it.

The real issue is this: Imagine you are an instructor who has been trying hard to get students in the habit of not putting masks on their foreheads. Then one of the students finds the training agency’s website and tells his fellow students, “Our instructor’s full of shit. The agency says this is okay.”

That’s not something a training agency, in particular, needs to be doing.

2 “Why wear a hood when swim caps are cheaper?”

It’s unusual to see a diver wearing a swim cap in lieu of a proper hood, and for good reason. A mask strap can easily tug on the swim cap in such a way that the diver loses both of them.

The better solution, of course, is to either wear a proper hood or beanie or, if pulling on the hair is a concern, to equip the mask with a neoprene foam comfort strap or strap cover. That’s what this photo should be showing.

3 “Mask straps don’t have to fit properly to work”

If you examine the photo carefully, you will see that the diver has her mask strap pulled so far off to one side, the snorkel keeper is preventing the split in the strap — which is supposed to be centered directly behind the diver’s head — from opening. This not only looks bad, it’s potentially uncomfortable and, worse, can lead to mask loss.

If you examine the photo carefully, you will see that the diver has her mask strap pulled so far off to one side, the snorkel keeper is preventing the split in the strap — which is supposed to be centered directly behind the diver’s head — from opening. This not only looks bad, it’s potentially uncomfortable and, worse, can lead to mask loss.

4 “It doesn’t matter how you mount your snorkel”

If you are going to attach a snorkel to your mask (which is an entirely separate issue in and of itself), you should at least do it in a way that allows you to immediately pick up the snorkel mouthpiece and begin breathing from it.

In this photo, however, due to the poor design of either the snorkel or the keeper, gravity appears to keep twisting the snorkel at least 90 degrees from its proper position. Granted, as with many of the problems identified thus far, this isn”t a huge issue (again, we’d barely bat an eye if this were someone’s vacation photo); however, it’s not something either a training organization or a major dive publication should be putting its stamp of approval on.

5 “A cheap, unbalanced regulator is good enough”

Unbalanced piston regulators have their place. To start, they are the ideal regs for deco cylinders, due to the ease which which they can be serviced and maintained for high oxygen concentrations. Depending on circumstances, they can also be an ideal rental reg for dive operations where guests never go deeper than 20 m/66 ft, due to their ease of service.

When I was running Lahaina Divers in Maui, we switched from Scubapro Mk X/G250s to Sherwood Bruts for just this reason. Understand, however, that we never took divers deeper than 20 m/66 ft and, if a diver were to need to share air, he would likely be breathing from one of our instructors’ alternate-air-source second stages, which would be attached to a high-performance, balanced first stage.

The problem with unbalanced first stages is that, due to the nature of the design, they must have substantially smaller valve orifices than balanced first stages typically do. This is generally not a problem in shallow water; however, if a diver starts breathing hard in deeper water, or if two divers are trying to simultaneously breathe from the same first stage, someone is going to end up being starved for air.

The problem with the photo is that it conveys the idea that cheap regulators are an acceptable investment for most divers. They aren’t. I doubt few divers really need a top-of-line reg; however, in general, they should at least get one with a balanced piston or diaphragm first stage.

6 “Your tank looks sexy in fishnet stockings”

Get a clue, folks. Dive centers hate these. They trap salt and moisture and make it difficult — if not impossible — to read hydro dates and inspection stickers.

If you want a clean-looking, unscratched aluminum cylinder, just get one that is either clear coated or, better still, uncoated. Unlike painted tanks, these will always appear scratch-free.

7 “It doesn’t matter what you do with your low-pressure inflator hose”

Most BC manufacturers include some sort of attachment or mechanism to help ensure the low-pressure inflator hose lies alongside the large-diameter oral inflation hose, and does not tend to pull the inflator off to one side, where it could be difficult to find.

This is more than just a matter of keeping things neat and orderly. With some regulators — notably cheap, unbalanced-first-models such as the one in the picture — there is a tendency to route the low-pressure inflator hose in the worst possible direction. Unless the BC provides a means to help keep that hose under control, the diver may find his or her inflator mechanism lost in action.

What’s ironic is that, the SeaQuest BC shown in the photo provides among the best means of doing so. On these BCs, the low-pressure hose literally snaps into the airway itself. In the photo, however, this has not been done, putting the diver at risk of not being able to find her inflator when needed.

8 “Loose-fitting wet suits are more comfortable”

Among the very first things new divers learn about wet suits is that, to work, they need to fit snugly. The one in the photo does not (the BC is also too big as well). Yet, the message the photo conveys to those who don’t know better is that this is okay.

9 “Your octopus is best left dangling”

Do we really need to say anything here? In order to do its job, an alternate-air-source second stage:

- Must be instantly accessible.

- Cannot dangle in a manner that would cause damage to the environment.

- Cannot dangle in a manner that would cause it to be damaged by the environment.

This one fails on all three counts.

Okay, are these faults really all that terrible?

None of these issues would be as much of a concern were this someone’s vacation photo. But this image has been placed front and center by both a major diver training organization and an otherwise respected dive magazine. This is both amateurish and unprofessional. It says, “This is acceptable behavior and this is acceptable gear.”

There is no excuse for this. Equipment manufacturers are more than willing to lend decent equipment for photo shoots, to help send the message that investing in something other than the cheapest gear possible — and using that gear correctly — is a good idea.

Even more troubling is the fact no one at either the agency’s headquarters or the magazine’s editorial offices saw this photo as a problem. This does not inspire a lot of confidence in their knowledge and professionalism.

Again, whether it’s a professional diving educator, a dive magazine or a diver training organization, anyone who positions themselves as a subject-matter expert and role model needs to be held to a higher standard.

Over the span of the past several decades, I’ve written several diving textbooks, run the art department at PADI and done similar work for other agencies. I’ve also edited five dive magazines and maintain over a dozen diving websites.

I can tell you, based on this experience, that this lack of attention to detail is not what is considered acceptable throughout most of the dive industry. In fact, had I pulled a stunt like using this photo back when I worked at PADI, they would have shown me the door in short order.

Yet, over a month after it was called to their attention, the training agency that first used this photo still had it at the top of one of the main pages of their website. (The dive magazine website no longer uses this photo; however, that may be a result of their having done a major website makeover.)

What is particularly troubling is that, in the case of the training agency, they are the only one with the gall to claim their divers are better trained than anyone else’s. Yet, as continued use of this photo shows, they might be better off just keeping their mouths shut.