![]() There’s a popular video entitled The Five Monkeys which helps explain why so many people do things that are completely unnecessary, while having no idea why. Although not based on an actual experiment, the underlying concept has been validated by other studies. The “Five Monkeys” concept applies to diver training as well. I continue to see instructors and training agencies teach skills or require equipment items that are either completely unnecessary, or which should have been superseded long ago by updated procedures.

There’s a popular video entitled The Five Monkeys which helps explain why so many people do things that are completely unnecessary, while having no idea why. Although not based on an actual experiment, the underlying concept has been validated by other studies. The “Five Monkeys” concept applies to diver training as well. I continue to see instructors and training agencies teach skills or require equipment items that are either completely unnecessary, or which should have been superseded long ago by updated procedures.

Here is the video:

Here are three examples of what I’m talking about. In each instance, I’ll cover what instructors typically teach or require, why doing so is out of date and what we should be teaching instead.

Regulator recovery

“In the unlikely event your regulator comes out of your mouth, you need to be able to locate, recover and clear it.” Okay, no argument there. At issue is how we teach it.

What students generally learn is that, as soon as their primary second stage goes missing, they are to begin exhaling a tiny stream of bubbles while fumbling behind them for the errant regulator. At this point it becomes a contest — i.e., will the student be able to find and clear the missing second stage before running out of breath?

Why do instructors teach this way? Prior to the mid-1980s, most teaching regulators had only a single second stage. This meant that, if a second stage went missing, the student’s only option was to find it. But even though training standards have required the use of alternate-air-source second stages for the past 30 years, instructors continue to teach this skill as though those extra second stages don’t exist.

Let’s think about this. What would cause a diver to lose a second stage in the first place? Reasons could include:

- A second stage is accidentally knocked out of or pulled from a diver’s mouth.

- The five-cent cable tie which holds the mouthpiece to the second stage fails, causing the second stage to pop out while the mouthpiece remains in the user’s mouth.

- The mouthpiece bite pegs tear off, making it difficult or impossible to keep the second stage in the diver’s mouth.

Notice that only the first of these three problems can be solved by locating the missing second stage. In the second and third instance, simply finding the missing second stage can still leave the diver with a regulator he can’t use…just as he is running out of breath.

I don’t know about you, but in 45 years of diving and over 8,000 dives, I’ve never had a second stage accidentally knocked out of or pulled from my mouth. I have, however, had mouthpieces and cable ties fail numerous times.

So what should we be teaching?

Something like this:

- If you do lose a second stage, start exhaling small bubbles and look down. If you have been maintaining proper horizontal trim, the missing reg will be hanging down in front of you rather than hiding behind your back.

- If you cannot immediately see or feel the missing second stage, pick up and begin breathing from your alternate-air-source. Doing so removes the time pressure of having to locate the missing reg before running out of breath. And, should you discover the missing reg is unusable, you are already breathing from one that works.

- While continuing to breathe from the alternate, locate the missing second stage using the reach or sweep method.

- Regardless of whether the missing reg is instantly visible or you have to hunt for it, do not put it back in your mouth until you check and make sure the mouthpiece is in place and the bite pegs are intact. If the primary second stage is no longer safe to use, continue breathing from the alternate and end the dive.

In an entry-level scuba course, there are generally two situations in which students would need to recover and clear a regulator:

- When regulator recovery and clearing is taught as a separate, standalone exercise.

- After completing a gas-sharing or similar exercise, during which students intentionally remove a second stage from their mouths.

Following a gas-sharing or equipment handling exercise, students shouldn’t need to do more than pick up the primary second stage you taught them to leave draped across their shoulders and resume breathing.

When taught as a standalone exercise, condition students to first locate and begin breathing from their alternate air source, and only then begin looking for the missing primary. As more and more instructors get away from the traditional “octopus” second stage in favor of a tech-style configuration, this becomes easier, as the extra second stage is located right in front of the diver, on a necklace, and is not something the diver has to hunt for.

Surface Swimming

Of all of the many places I’ve had the opportunity to teach, among my favorite is Haigh Quarry in Kankakee, Illinois. It has unusually clear water for a rock quarry, is easy to navigate and features an abundance of fish, wrecks and artifacts.

One of the best things about Haigh Quarry is the ease with which you can enter. Using the old road into the quarry, you just walk into chest-deep water, don your fins, stick your regulator in your mouth, then swim down the embankment to the nearby platform. From there, guidelines lead in multiple directions to various points of interest. Returning to your starting point under water is equally as easy using just the guidelines and natural navigation.

So, in other words, there is never any need to swim long distances on the surface when diving Haigh Quarry. At least that is what my students learned. But, apparently, I was among the few instructors who taught that way. For reasons passing understanding, most instructors would teach students to enter the water, then swim on the surface for 200 feet or more before descending down a line.

Make no mistake, there are several critical surface skills new divers must master prior to certification, including:

- Swimming at the surface, both face down, breathing from a snorkel, and face up, breathing from their nose and mouth.

- Equipment removal and replacement.

- Cramp releases and tired-diver tows.

At the same time, it is equally important that students learn that being on the surface is something to be avoided unless absolutely necessary. Why?

- It is generally harder to swim on the surface.

- Being at the surface can expose students to stronger currents, waves and boat traffic.

- The surface is where most accidents happen.

Available evidence suggests that, even when problems begin under water, most accident victims make it to the surface before losing their battle to stay there. In other instances, it is the higher level of exertion or the stress of fighting waves and currents that can provoke a cardiac event or fatal panic. Overall, it appears divers are safer being under water with plenty of gas to breathe than they are struggling to stay at the surface.

So, if the surface is a place divers should learn to avoid, why does entry-level training seem to place so much emphasis on being there? To understand this, you have to go back to diver training’s roots in Southern California. For the ten years from 1978 to 1988, I got to live and teach in LA and Orange Counties. It was a valuable experience for many reasons — not the least of which was that it provided an understanding of why I’d been taught to teach a certain way in mid-Atlantic rock quarries which seemed to have no relevance to the local environment.

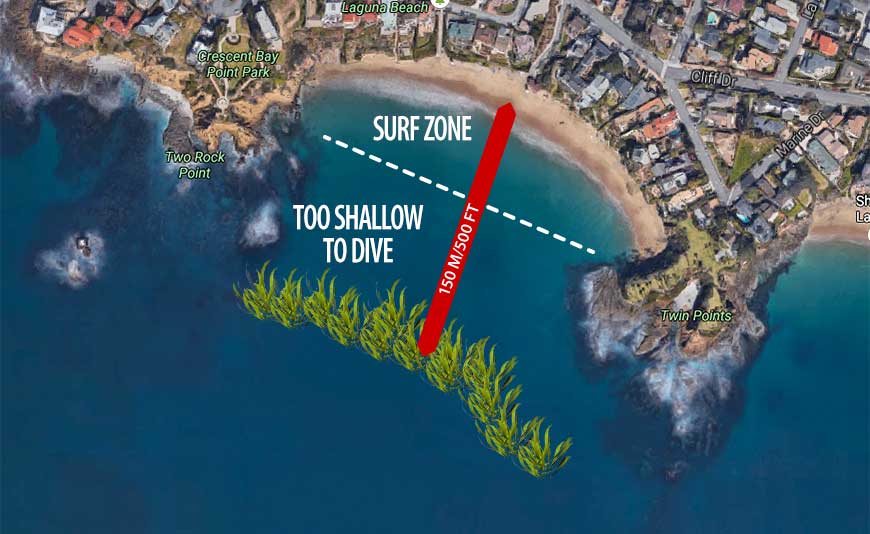

California beach diving is unique in many respects.

- To start, you almost always have to enter through breaking surf. The surf zone can be anywhere up to 50 m/150 ft wide.

- Once you make it through the surf, you frequently can’t descend, as the water is still too shallow and surgey, and there is nothing to see until you get out to the kelp beds.

- As a consequence, long surface swims are an integral part of California beach diving, especially in the southern part of the state.

As I mentioned earlier, diver training traces its roots to Southern California. At one time, nearly all major training agencies were based there. Because of this, there are things which are unique to teaching off Southern California beaches which, somehow, have become ingrained in how most instructors teach — even though they have little relevance elsewhere. The need to do long surface swims is just one of these.

So what should we be teaching?

As mentioned earlier, there are surface skills that all new divers need to master. At the same time, however, it is important to teach students to avoid surface swims whenever possible, and to always surface as close to their exit point as they can. This can include:

- Establishing not only minimum ascent pressures, but turnaround pressures designed to ensure students have sufficient gas to return to their exit point under water.

- Establishing a navigation plan that helps ensure students will finish their dive at or near their exit point.

- Increased emphasis on compass and, especially, natural navigation.

Ideally, every student should have the opportunity to lead at least a portion of a dive, with the goal of getting the group back to the exit point. If not during the Open Water Diver course, at least during the Advanced course. The last thing you want to do is turn students loose following certification, having never done anything other than follow an instructor or divemaster around. And you do not want them to blindly associate the surface with safety.

Snorkels

Somehow, over the years, I’ve gotten the reputation for being anti-snorkel. I’m not. In fact, I wear a snorkel — every single time I go snorkeling. And, if I’m diving in a body of water substantially larger than a freshwater spring, odds are I have a snorkel with me. Folded up. At the bottom of my thigh pocket. Beneath my SMB, signal mirror and whistle — items I’m more likely to actually need, should I find myself stranded at the surface for any period of time.

What I have an issue with is the notion that the average scuba diver needs to own something resembling an overgrown sex toy and keep it strapped to his mask at all times — even though, if he is diving intelligently, the odds that a “dorkel” will actually be needed are slim to none. Wearing an unnecessary snorkel strapped to your mask can cause all manner of problems, from entanglement to drag, poor mask fit and general distraction. Yet the major training agencies cling tenaciously to the notion that, if you do not have a dorkel strapped to your mask, you are somehow unsafe.

So where does this idea of constantly wearing a snorkel while scuba diving come from? Surprise! It’s Southern California…again. As mentioned earlier, Southern California beach diving generally entails long surface swims. Prior to the introduction of jacket-style and back-inflation BCs in the 1970s, there was simply no way to get your head out of the water far enough to breathe comfortably. Therefore, if you were diving a horse-collar BC — or, prior to the early 1970s, no BC at all, a snorkel was essential.

Even today, if you dive in one of the few places where it is helpful to be able to swim face-down on the surface while conserving air from your tank, having a snorkel strapped to your mask might make sense. Such places are a lot less common than you might imagine, though.

There are some interesting parallels between snorkels and BC oral inflators. Aqualung, recognizing that the only time a diver might actually need to orally inflate a BC was in the event of power inflator failure, introduced their i3 system, a streamlined inflation/deflation mechanism that does away with the traditional oral inflator. In its place is a separate, compact inflation tube that tucks away in a pocket until needed…which, for most divers, will be never. Kind of like the need for snorkels while scuba diving.

So what should we be doing?

We need to be taking the same approach with dorkels that Aqualung did with the traditional BC oral inflator. Do away with the monster dildo strapped to a mask and replace it with a compact, folding snorkel that stays in a pocket until needed (if ever). Folding snorkels have the added benefit of being substantially less expensive. The money they save divers can go toward things like better quality fins or a dive computer.

Think about it. You use your fins 100 percent of the time; when was the last time you actually needed a snorkel? It makes more sense to buy the best fins you can afford and to spend as little on a snorkel as possible.

If you would like to read more on this topic, see the accompanying article, The Sad, Sordid History of the “Dorkel.”

“But we’ve always done it that way”

This sort of “logic” has been used to justify everything from slavery to bloodletting with leeches. It has no place in diving. We can do better. We need to do better. There is no excuse not to.